Last month, I was invited to open the 8th Forum for design educators in Mí©xico. The forum was organized by COMAPROD, the evaluation body of design academic programs in the country, and the largest organizations of design schools: Encuadre (focused on Graphic Design programs) and DI-Integra (focused on Industrial Design programs).

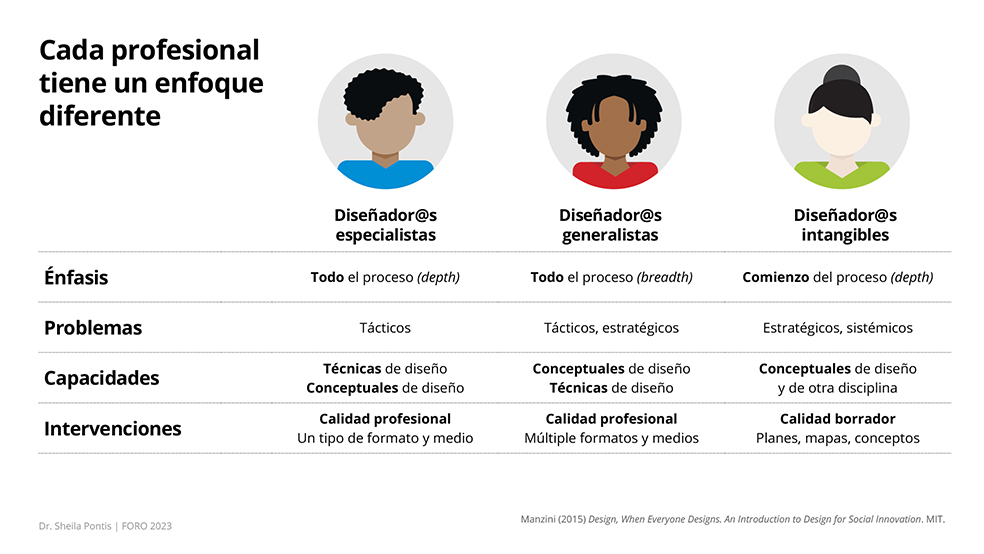

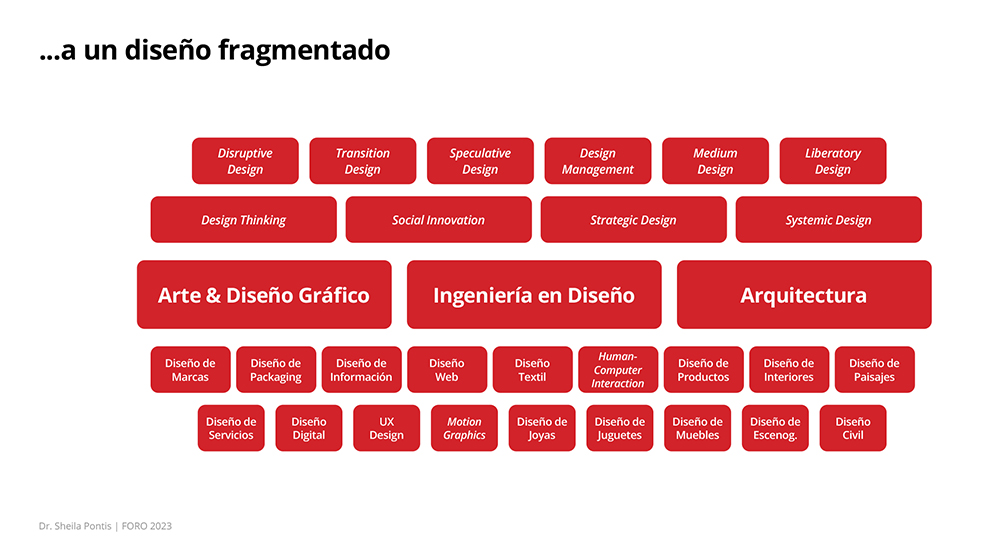

My talked provided a short historical overview of design practice, research and education, from its origins with the Industrial Revolution to the present day, followed by an analysis of the current state of design. Expanding on Ezio Manzini view of design, I proposed a fragmented picture of design professional practice, where what started as three large areas of Design – Art & Graphic Design, Industrial Design, and Architecture – now looks fragmented with multiple specializations, each having a different goal and demanding a unique set of skills. Within this fragmentation, we can identify three types of design:

1. Specialist design: It focuses on the entire process in depth, commonly to work on tactical challenges. Design skills and technical knowledge are their strength as well as the creation of interventions within a specific design specialization with professional quality.

2. Generalist design: It focuses on the entire process but with less depth than specialist design as it deals with both tactical and strategic challenges. Its strength is more about breadth and the generation of concepts and prototypes than on the creation of a particular type of professional looking interventions.

3. Intangible design: It mostly focuses on the beginning of the process working on strategic and systemic challenges. Collaborative work with other disciplines and sectors is essential to gain understanding of the challenge at hand and generate design concepts and intervention ideas, like blueprints and journey maps.

The fundamental difference among the many fields of design is their level of connection with more traditional design knowledge (vertical axis – third image above), referred to uppercase Design. For instance, specialist design demands a deep understanding of design knowledge, skills, and tools. On the other hand, lower case design, refers to intangible design, which demands a large proportion of knowledge from other disciplines beyond design – this means that these designers don’t need a design background.

For the last five years, the big question in design education has been on which of these design paths should courses and programs focus on. In this new landscape, to better prepare the next generation of designers, educators should first gain a clear understanding of each type of design. Specifically, they should become familiar with their emphasis, common challenge types, competences and skills needed, and types of interventions that professionals would be most likely creating. Without this clarity, it would be impossible to provide students with an accurate and realistic picture of design as well as adequately equip them to succeed in the work path they join after graduation.

Equally important is to adopt a transdisciplinary approach to design education. This means to build teaching teams that integrate individuals with academic training, design practitioners, as well as professionals from other sectors and industries. Students should also play a central role and contribute to shape their learning experience. One way to do this is working together with the teaching team to shape the syllabus.

Building on Sir Ken Robinson’s education pillars, regardless of its focus, any design program should integrate two types of knowledge: essential ingredients – mindset, citizenship, creativity, and collaboration – and specific ingredients – design process, tools, practice, and knowledge from another discipline. While the foundation is the same for any design path, each path requires a different teaching emphasis. That is, the proportion of specific ingredients should vary according to the needs of each path. For instance, a program focused on information design would have a stronger emphasis on tools and practice, than on teaching knowledge from a non-design discipline, while a program focused on design social innovation could have multiple courses on social design and policy making.

A school can decide to teach only one type of design or offer programs for all three types of design. Teaching a program on social innovation or strategic design is not better than teaching only about graphic design or UX, what matters most is to:

1. Understand what are the characteristics of each type of design: emphasis, problems, capacities, interventions.

2. Work with a teaching team that is transdisciplinary: involving academic designers, professional designers, professionals from other sectors, users, clients, stakeholders.

3. Accurately communicate expectations to students: Knowledge upon graduation, roles in work teams, types of challenges they would be equipped to work in, potential job opportunities.

At the end, there are no shortcuts to become a successful designer. It takes a long time, committed effort, and sustained dedication to achieve positive impact in the world with D/design.

Leave a Reply