Writing a book is not always an easy journey – at least this has been my experience with all my books. Here are some of the learnings from my last book.

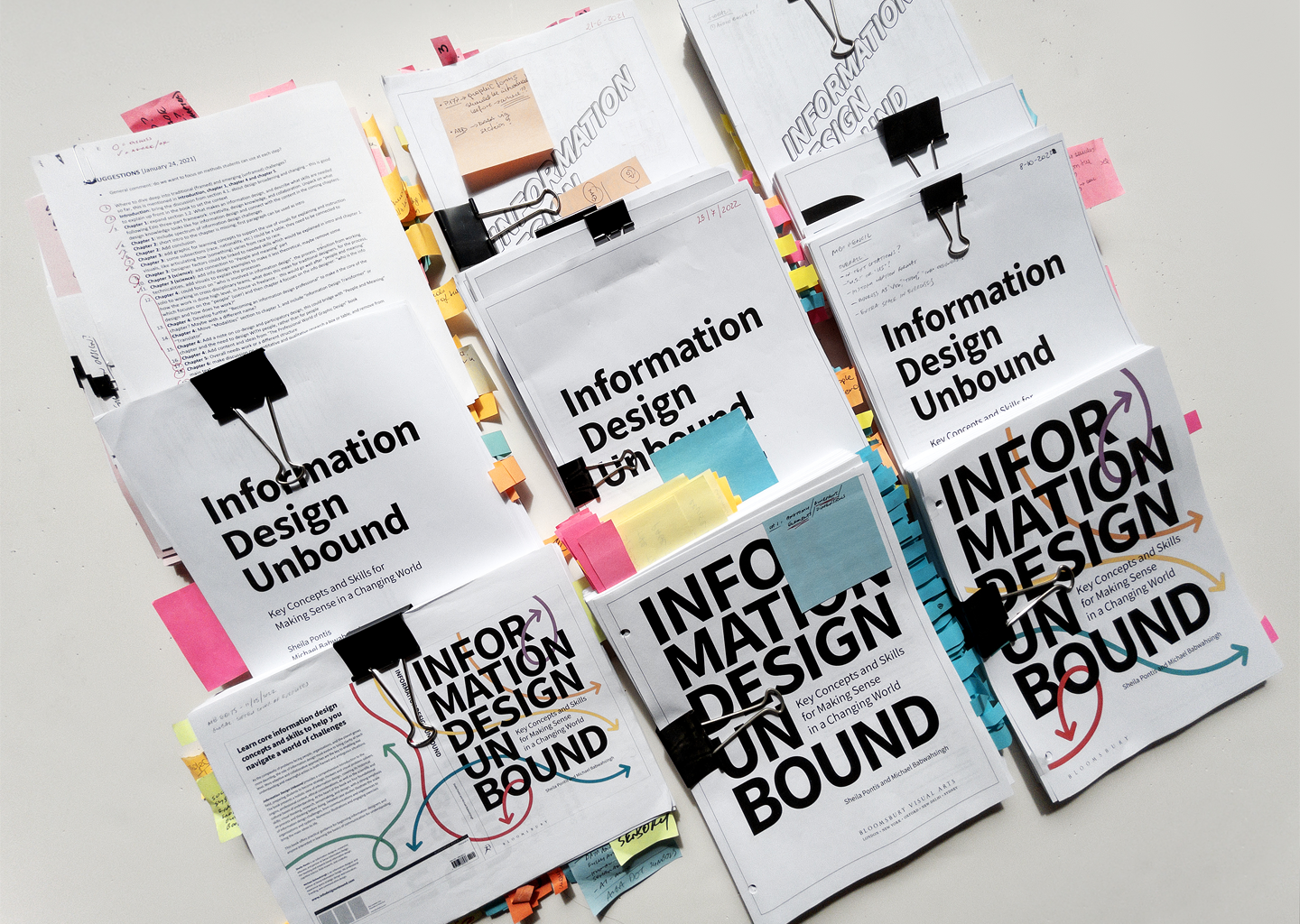

Information Design Unbound was initially conceived a long time ago and was in the making for over 6 years, during which COVID and other life changing events occurred. There were many factors that played a role in the process, from publisher’s constraints (timeline, page count) and contributors’ materials to the actual writing of the book. I unpack five of them below that could provide guidance to most book-writing experiences.

1. Unique message. Having clarity on what you want to say is essential to not only write the book proposal but it is also the compass for the rest of the book. While we had a clear primary audience – undergraduate students, and one of our main goals was not to rehash ideas and concepts that have already been discussed multiple times before and published in several books, we didn’t have a sharply defined point of view at beginning of this project. Rather, we did know that we wanted our book to be a new contribution to knowledge that helped advance the community and practice. So, initial conversations were focused on sharpening our point of view and identifying aspects of information design that are relevant for today’s needs. We also focused on crystallizing pedagogical features of the book, such as defining how information design could be taught to a pool of highly diverse students. When you embarked in a long journey, like this one, it was helpful for us to remain open to changing our minds and adapt the message to reflect your new thinking, even if this would involve more work and writing initial chapters.

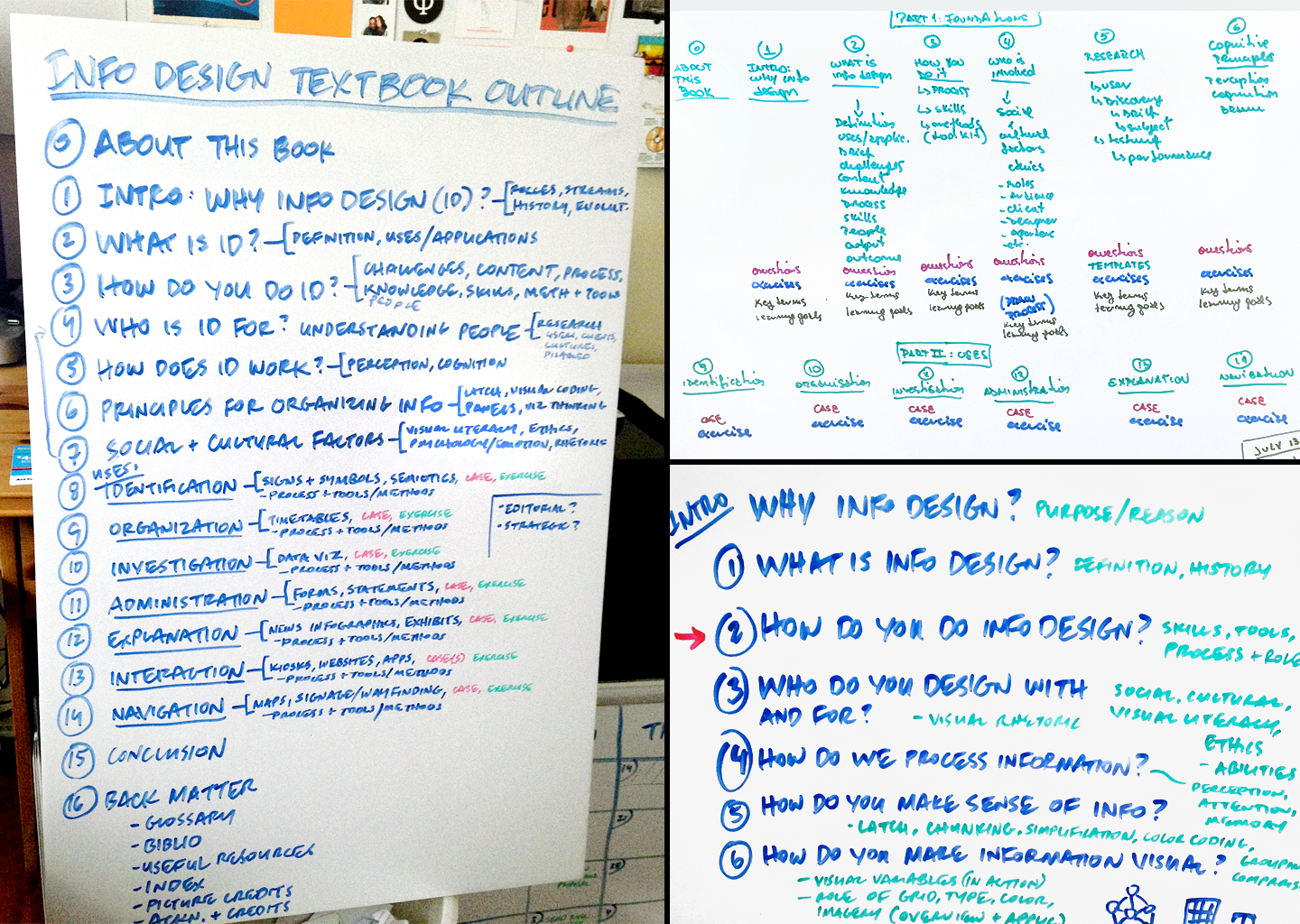

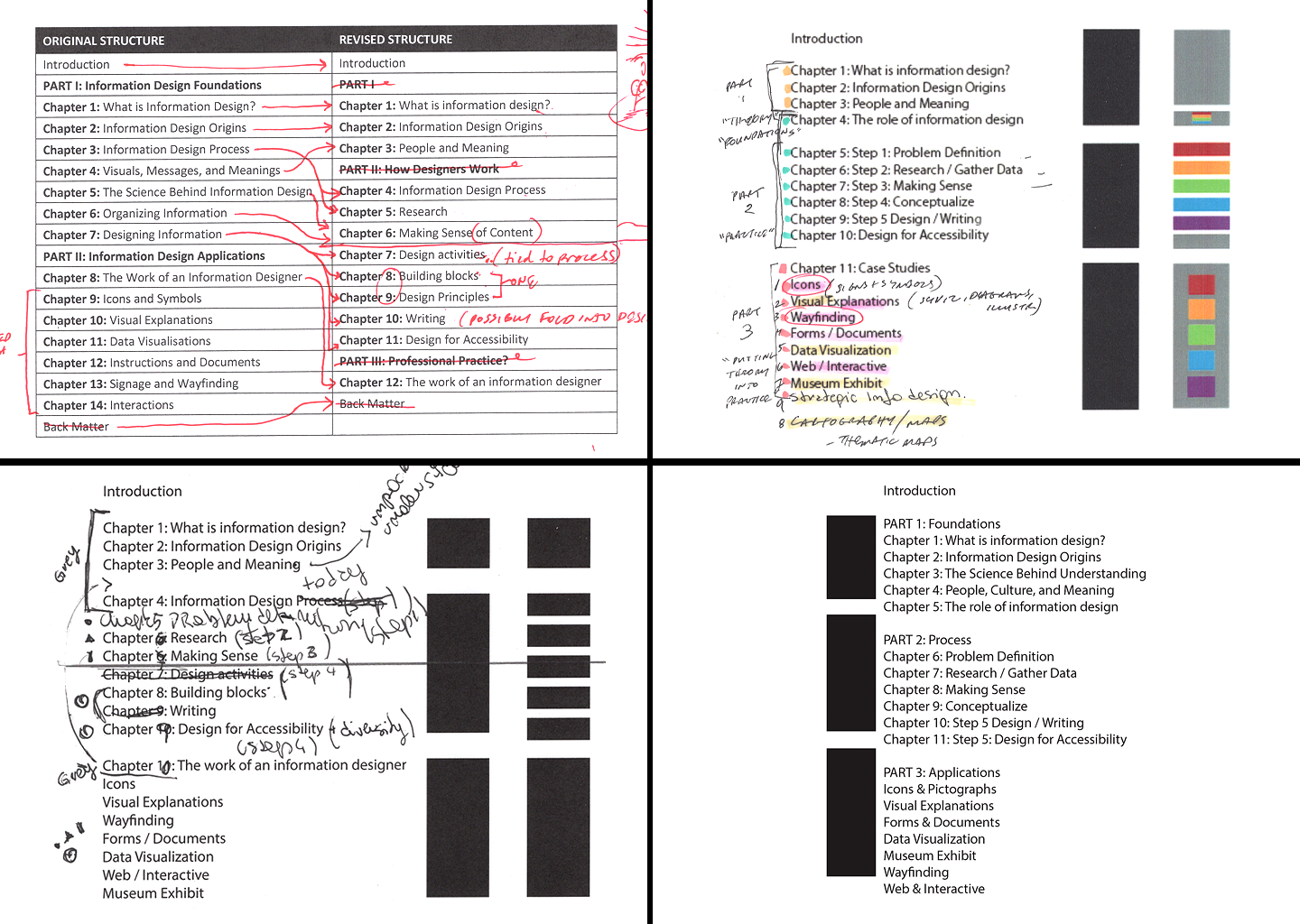

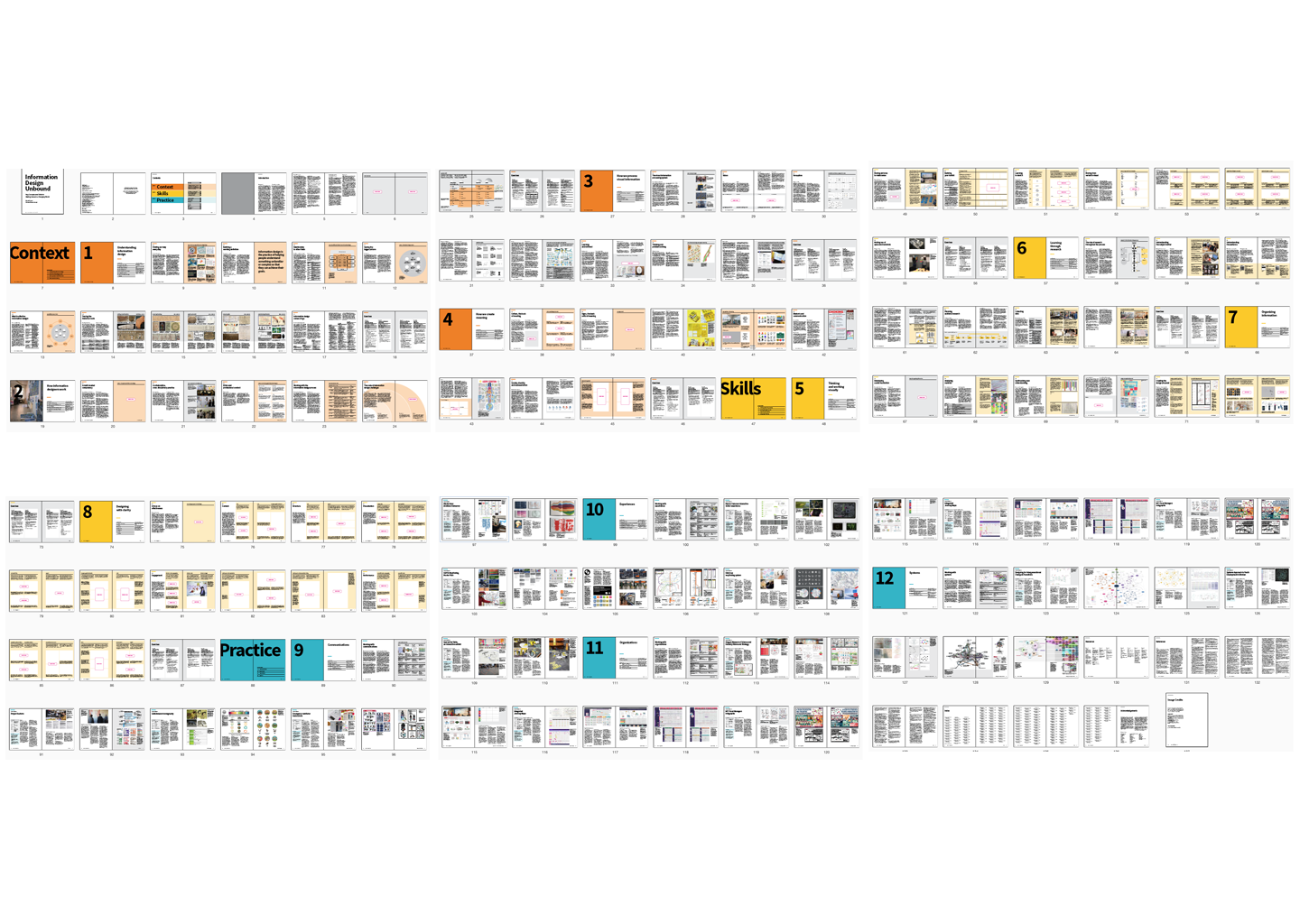

2. Clear structure. With clarity on the message, the second key step was to define a structure that would help us organize the content in an introductory and pedagogical way. As our approach is a little different from traditional design education and our views on information design practice are broader, it was challenging to arrive to the final structure and identify a sequence of ideas that clearly conveyed our message. How much content is enough content? What are the main concepts of each chapter? What are the main teaching objectives? Which concepts should be introduced first? How can we organize content so it is easy to access in a classroom? These were only some of the questions that we had to answer. Book dimensions and page constraints were a big part in the decision-making part of the process. For instance, while we negotiated more pages (from 224 to 272 pages), we had to reduce the number of chapters from 16 to 12. This decision also helped us go more in-depth with each concept.

3. Tailored communication. Our book is heavily visual with 400+ images, including illustrations created by us as well as project images from contributors. We wanted to both illustrate key concepts with real world projects and showcase the breadth of the practice. This meant to find people engaged in information design work working in different industries and sectors as well as in different types of projects. This task took a substantial amount to time. First, we had to identify potential projects that would convey the concepts we needed to illustrate. We took great care to examine organizations and design studios of different sizes, and individuals in different parts of the world. Then, we reached out to each potential contributor and explained our needs. Finally, we requested the specific materials and organized follow up conversations when needed. Tailoring emails to the specifics of each project was essential to receive a high quantity of positive responses. Specifically for the case studies – where we showcased complete projects rather than only one image, it was important to ask questions and learn more about their process. Equally essential was to track each step in the process, provide clear but realistic deadlines, and gently chase when needed. The final list of contributors has more than 65 names, but the initial list had more than 200 possible projects.

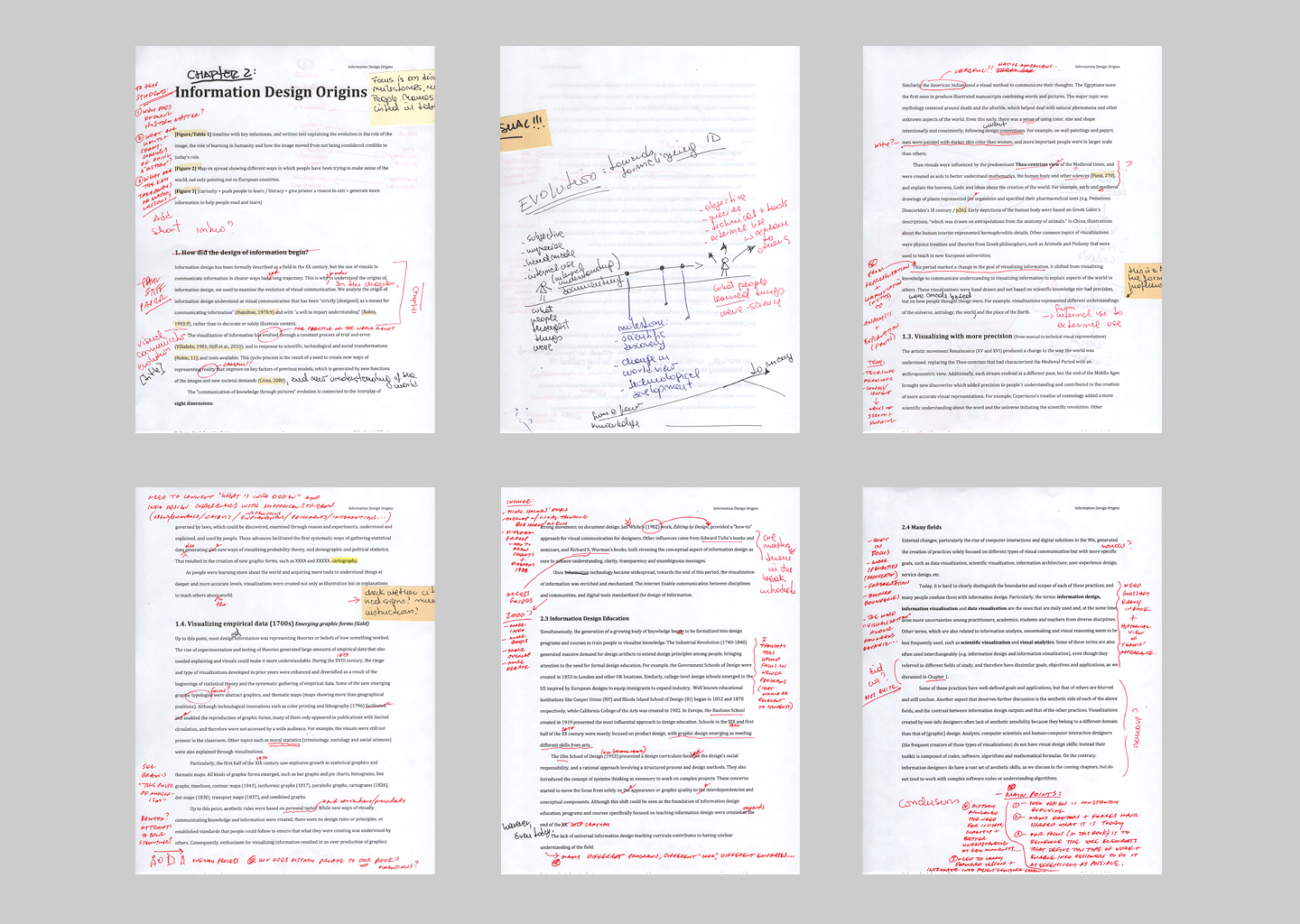

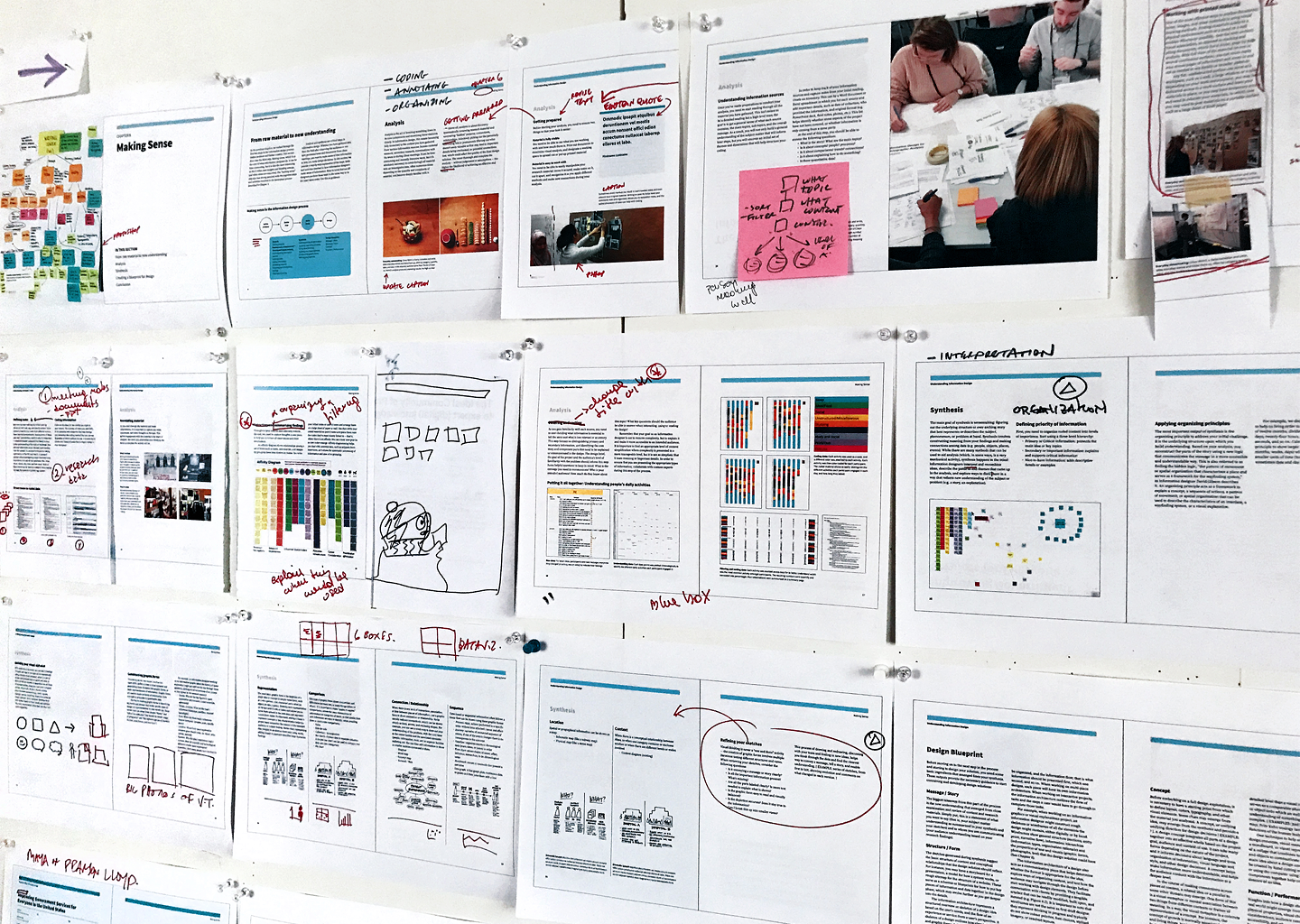

4. Multiple iterations. As with any creative project, getting it right takes time and great effort. We followed a systematic iterative process. For instance, each chapter was initially written in Microsoft Word (later converted as Gdocs for easier collaboration) without images; these included chapter outline, key concepts, possible exercises, and main content. After several rounds of back and forth were drafts were printed and annotated, when we both were happy with the content, we started working in InDesign directly creating spread layouts as the smallest units. Both design and content were also adapted with each round of reviews. Once all content was organized in the layout, it had further rounds of reviews. With each review, text was edited to fit the respective page layouts and adapted based on the visual material that we had, making sure there were no repetitions, text and visuals were complementary, and there was consistent use of language and terminology. We also paid attention to composition and went from general to specific checking that the message was coherent within each chapter as well as within each Part and throughout the entire book.

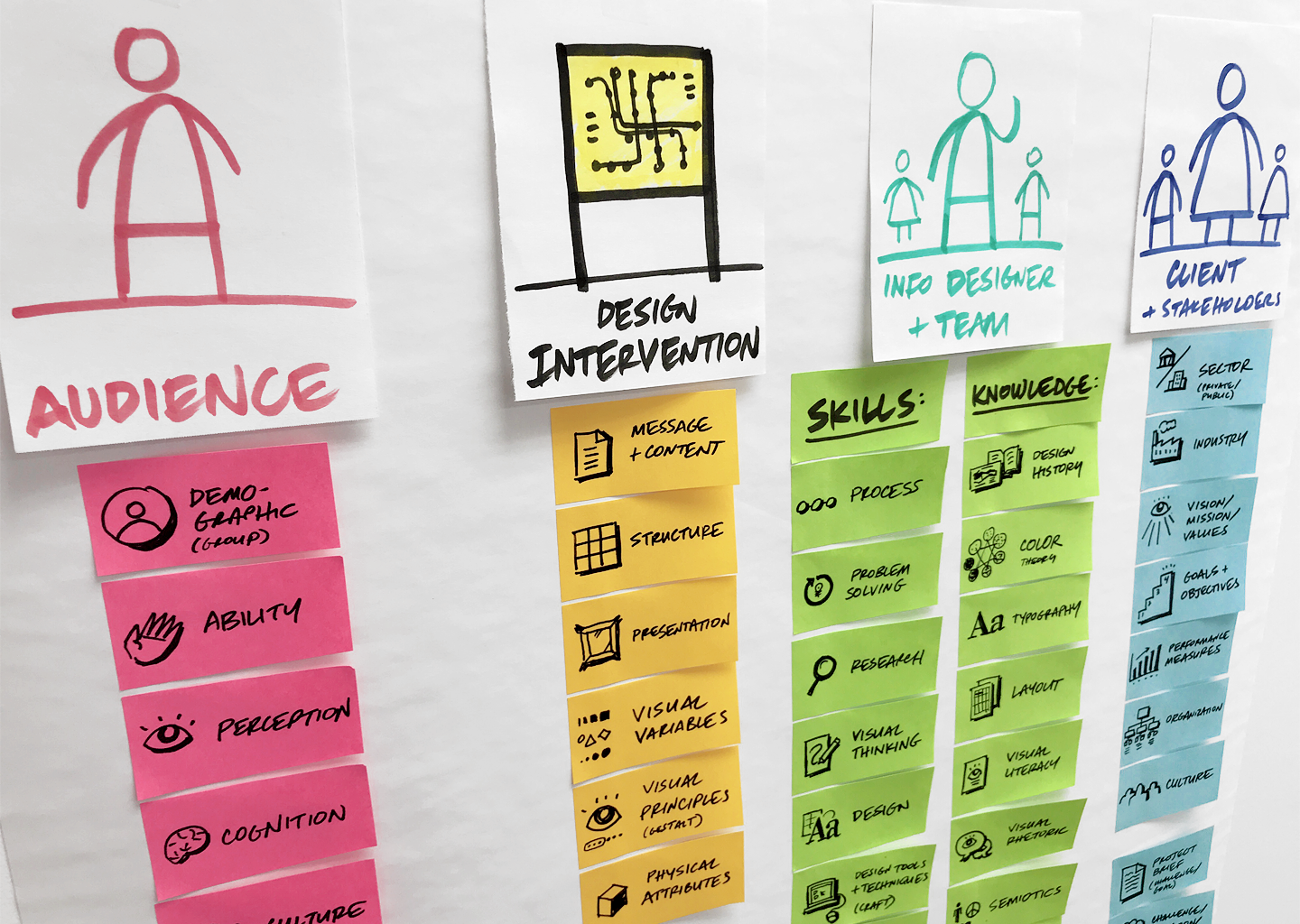

5. Think visually & aloud. Writing a book solo and co-writing a book are two different experiences. In this case, we were two authors, which greatly enriched the final output but also added some spice to the process. Multiple conversations were indispensable to clarify concepts and create a unified voice and message. These conversations also helped each of us better articulate and explain our thoughts, which elevated the quality and depth of the concepts and ideas included in the book. Thinking visually through sketches, charts, and drawings, was a must to make sure we were on the same page. Being transparent throughout the process by indicating the status of each task was also key to ensure that the other person knew what to do by when.

You can learn more about the design process in the book website.

And if you haven’t already, get your copy here!

Leave a Reply