This has been a busy year. Among other things, in the Fall semester, I took on the challenge to lead the Critical Design & Research Seminar course, which prepares MFA students from the Experience Design and Information Design & Data Visualization graduate programs to start working on their final thesis. For different reasons, the experience was a learning journey for both the students and me.

First, the size of the group – 18 students, with each of them working on a different topic, demanded a lot of creativity to use the time productively and efficiently as well as to adapt individual exercises to group formats. Then, the little understanding or misunderstanding of what researching on design involves. Pursuing a masters thesis is not an easy job because it is an open-ended, long-term project in which the student needs to make many decisions: topic, audience, methods. On top of that, there are “rules” that need to be followed to make the research credible and valid. Even today, this way of working is unfamiliar to many design students.

These are five learnings from teaching this course that could be helpful to keep in mind next time:

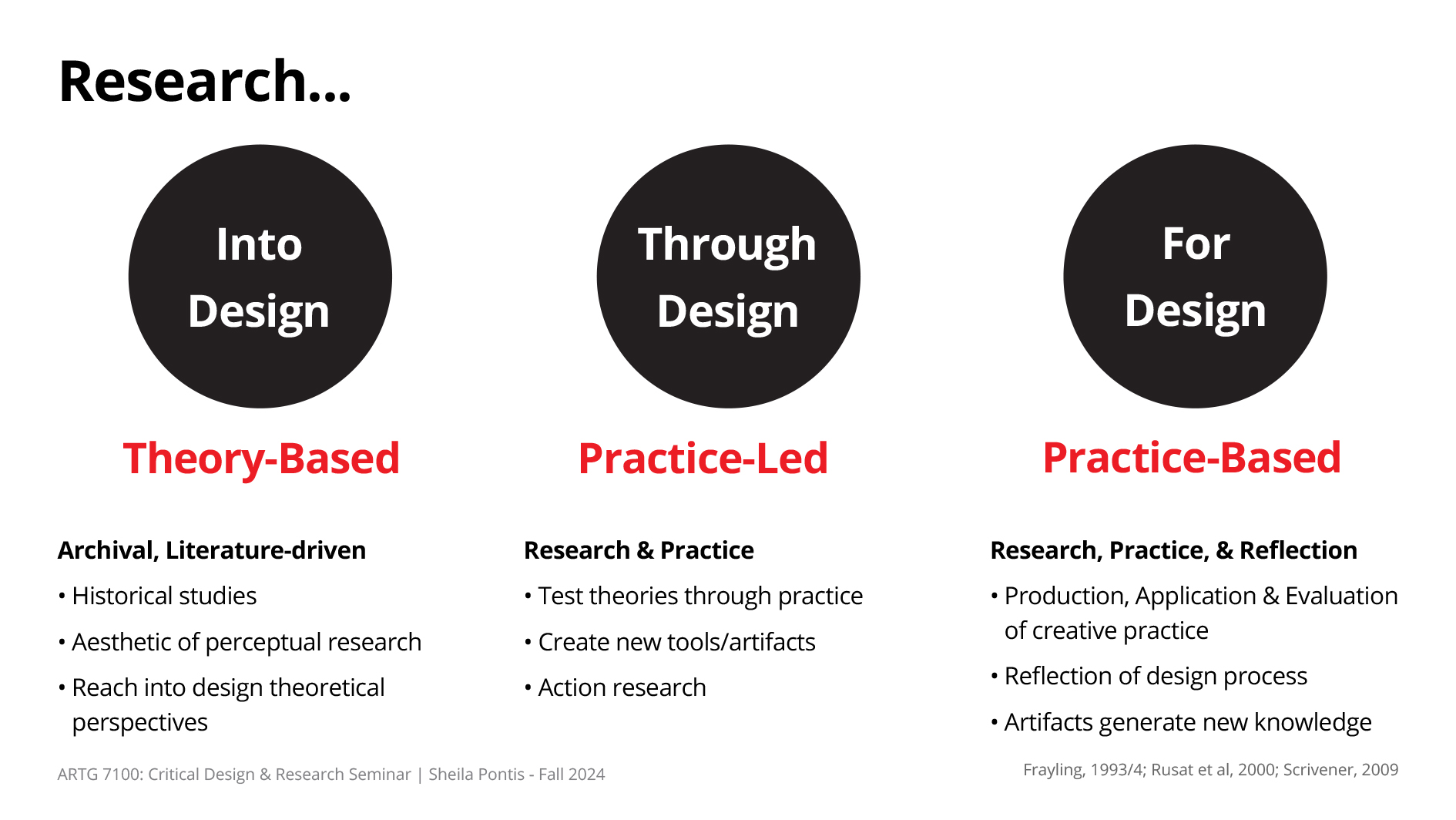

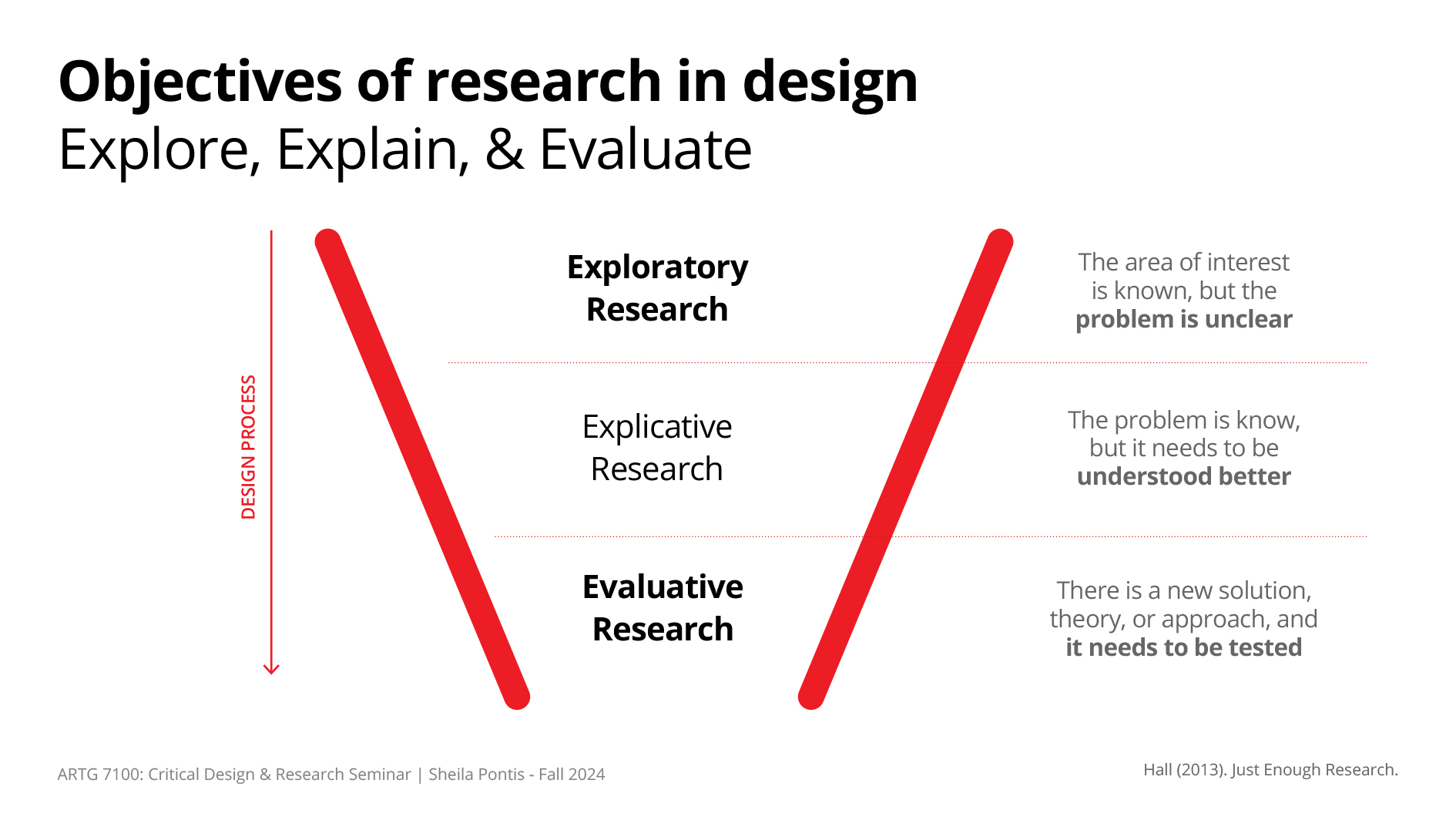

- Start with the basis: Research on design can be hard to understand as there are many ways of doing it, multiple approaches, and different modalities – all equally valid. Even if students have used research for a project, research for a masters thesis is a little different. Articulating these differences early on is essential to build a shared understanding and vocabulary.

- Teach the rationale and principles, not only the methods: “I want to do interviews,” “I will conduct participatory workshops,” “My thesis uses participatory design.” I heard these expressions from students every class, but when I asked why they wanted to use interviews rather than observations. Or what they wanted to learn from participants – they couldn’t answer. Students’ tendency is to pick the method that they have heard a lot about, even though it may not be helpful to answer their research question. It is important to start by defining the goal they want to achieve or what they want to learn more about, and then understanding the specific goal of each method.

- Put theory into practice to increase comprehension: Explaining a method or a framework alone is not enough for students to grasp what it means, even if they enthusiastically nod to indicate they understood it. Only when they start grappling with the new concept, they would realize whether or what they don’t understand.

- Provide structure. This has been the most helpful pedagogical approach. To make the abstract nature of research more tangible, early on in the semester, I gave students a little template with five questions they should answer with their thesis proposal. This template became instrumental for students to frame their thesis project and ensure they weren’t leaving out any important component:

- What is your research topic? Be general

- What is the problem, area or idea you want to investigate further? Be specific

- What will you investigate? That is, people, projects, objects, services, etc.

- Who is your audience? The specific population you will investigate

- What is your research question? Combine problem and audience with what you will examine?

- What is the expected output? The design, theory, tool, etc. you want to create

- Allocate ample time for each exercise: The simplest activities take longer than planned. Many students struggle with making decisions and committing to a topic or articulating the research question. This makes most activities challenging. Also, developing a research mindset implies a new way of looking at a project: answering many “why” questions, making all decisions explicit, and building arguments based on evidence, rather than personal opinion. Learning how to integrate these tasks into the process takes time and practice.

- Connect exercises with their own research: Examples are king as they help students better understand abstract concepts and see them in action. However, it is even more helpful for them when they engage in exercises using their own research. This increases motivation and commitment.

Supporting in-class instruction

Throughout the semester, I organized four events which serve multiple purposes. On the one hand, they were opportunities for students to talk about their projects and receive feedback from other professors and peers. They also provided a window into former master students who already completed their thesis. On the other hand, they also shed light on the dynamics of the advisor-advisee relationship and help students learn more about what to expect from that dynamic.

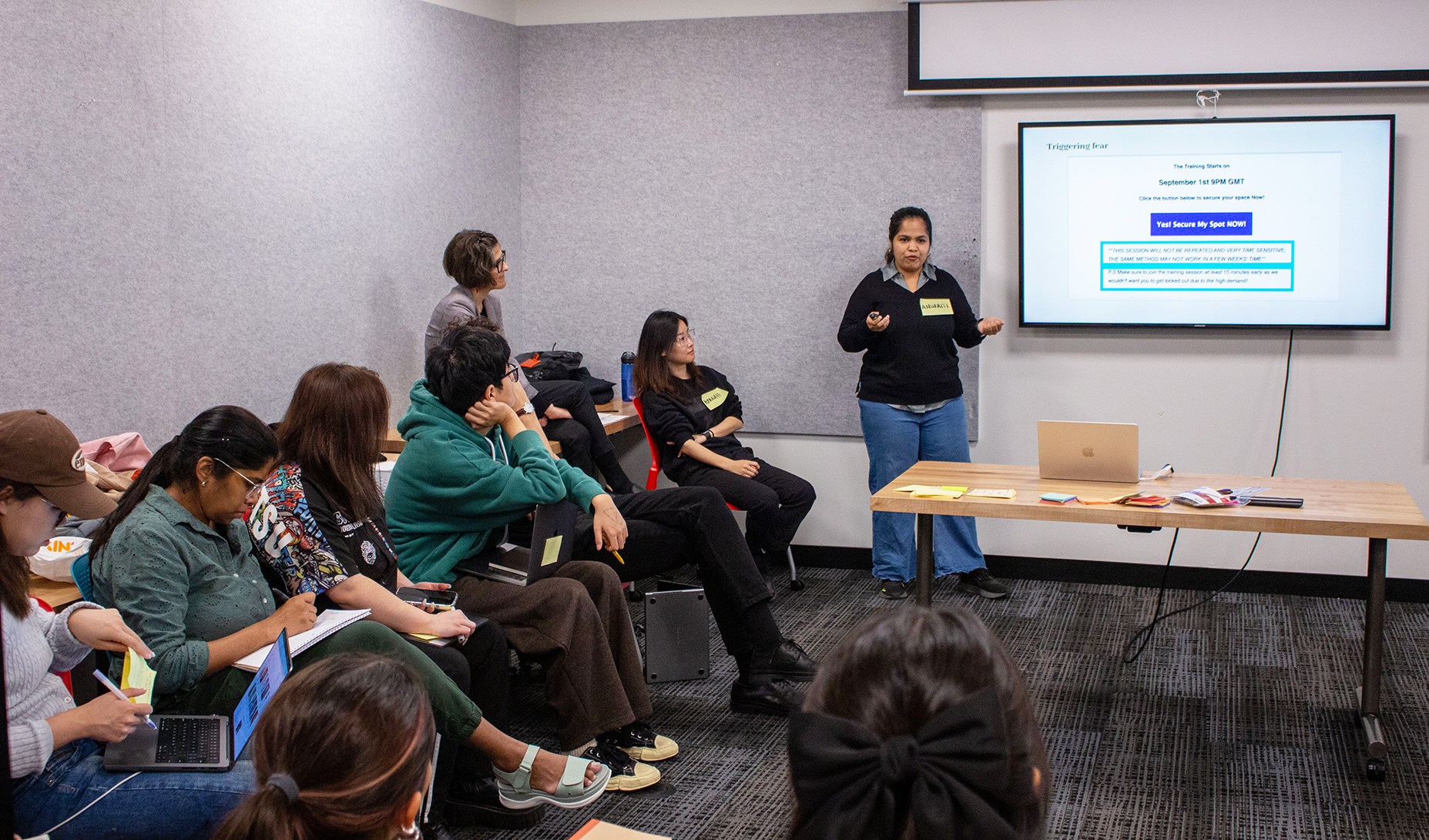

Former Master Students’ Thesis Panel: Early in the semester, three former master students from MIT visited the class and presented their thesis journeys: Hannah Oh, Saloni Bedi, and Anukriti Jain. The session was great in offering three very different approaches to design research, with different research questions, methodological approaches, and outputs. Seeing the end point was illuminating for the MFA students as it made the task more tangible.

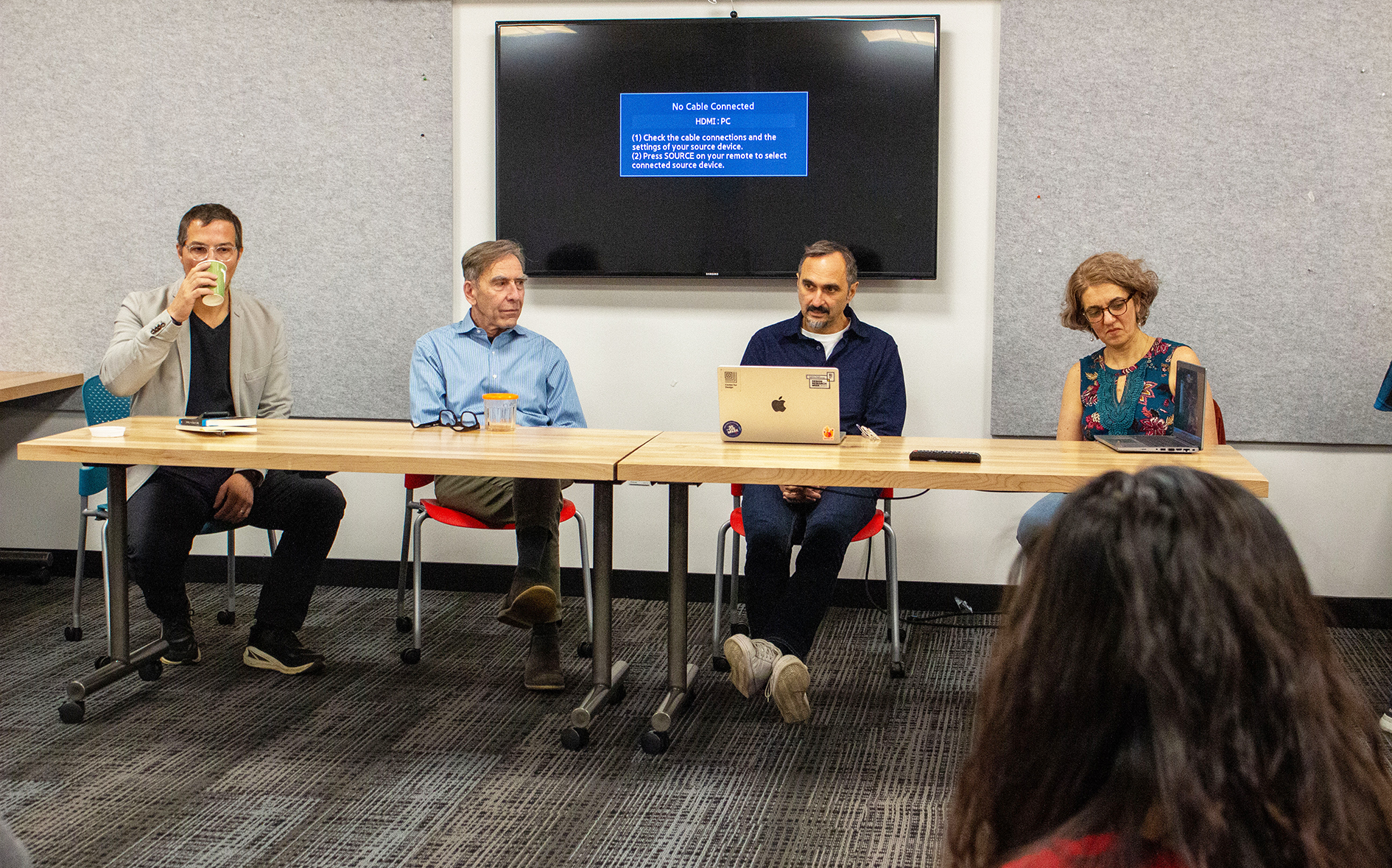

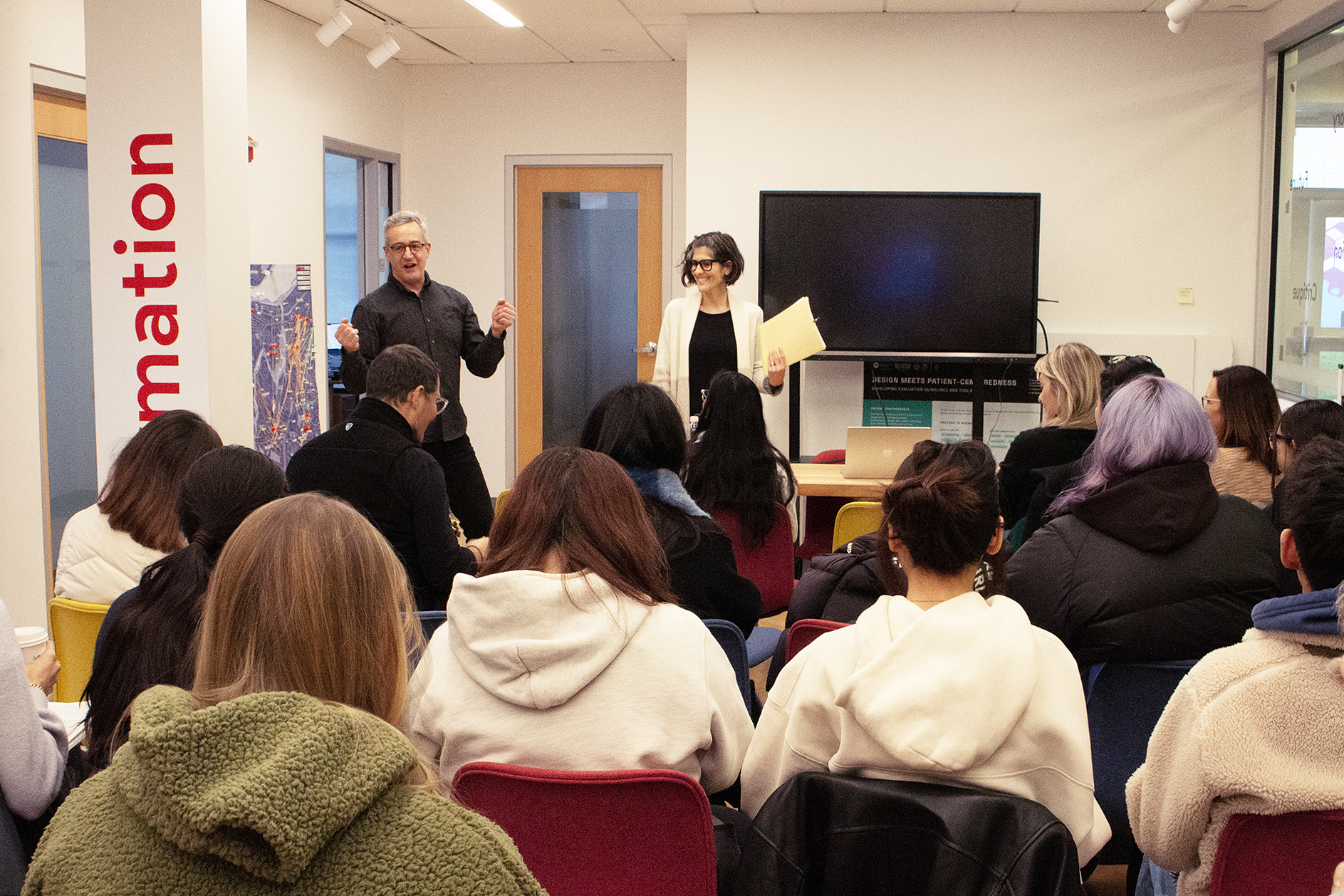

MFA Thesis Advisors Panel: Four professors from Northeastern University who are also serving as thesis advisors participated in the panel (from right to left in the image): Associate Teaching Professor Najla Mouchrek, Professor of Design Paolo Ciuccarelli, Professor Thomas Starr, Associate Professor Kristian Kloeckl, and me (on the screen!). They shared their experience supervising MFA theses and working with advisees and also answered students’ questions submitted in advanced. This session was really effective in exposing students to different, yet complementary views on what an MFA thesis looks like and advisors’ expectations.

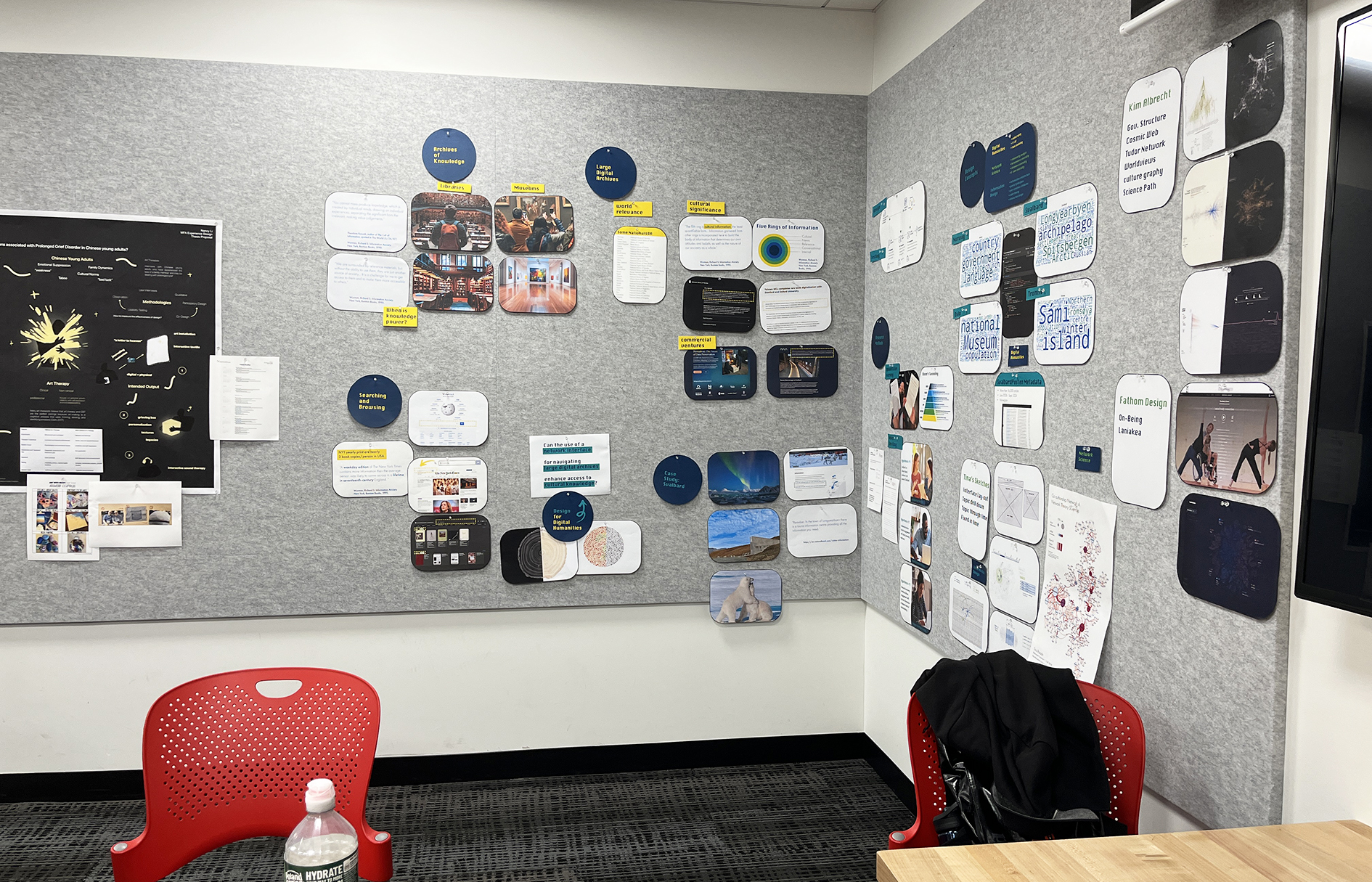

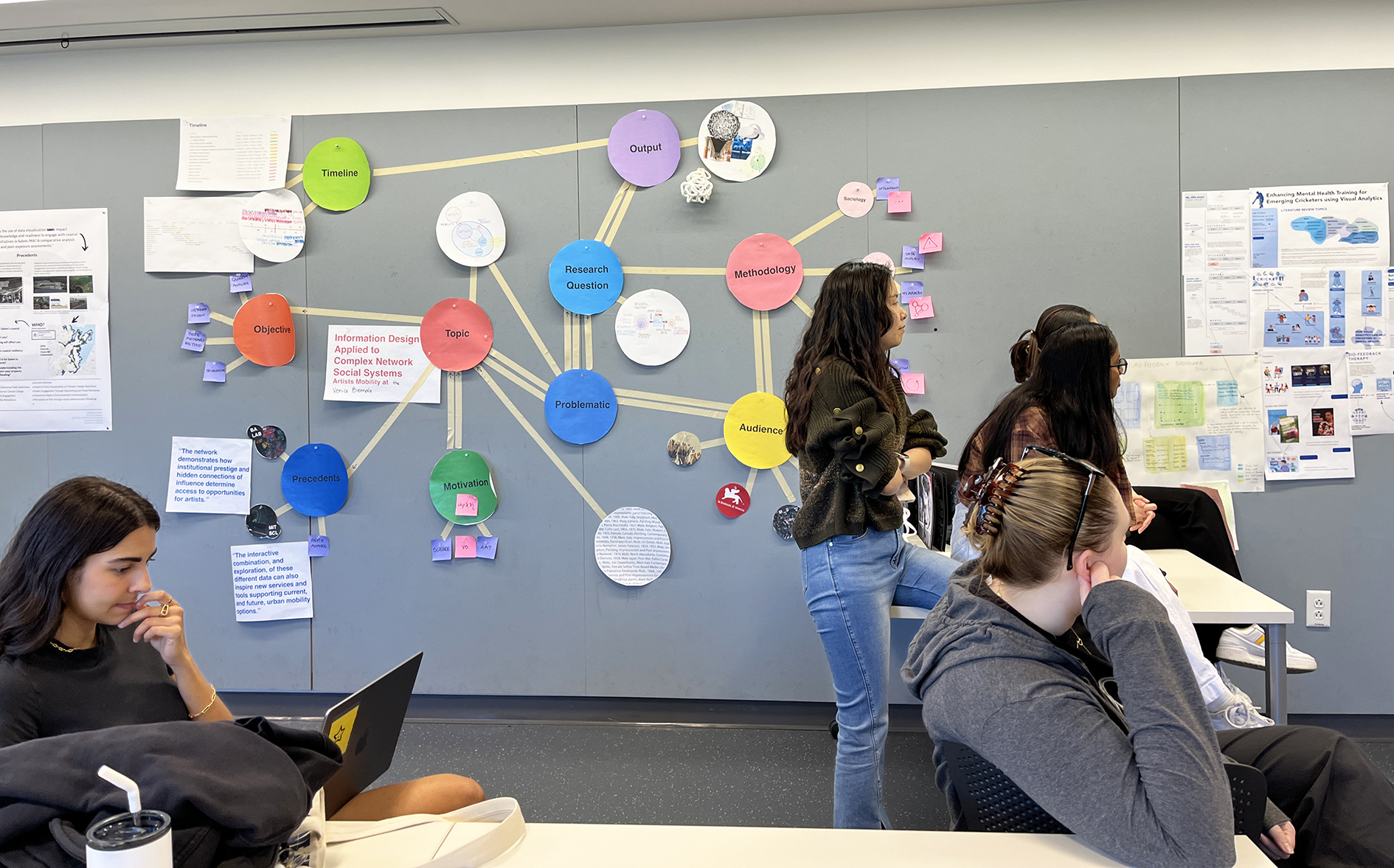

MFA Thesis Proposal Mid-point Review: Mid point in the semester, students had no more than seven minutes to present their project to the rest of the class. For this presentation, rather than creating a traditional PPT or PDF, students used imagery to help convey their projects. This was the first time that students had to articulate the whole story aloud and receive feedback. This session was not open to the public.

MFA Thesis Proposal Presentations: At the end of the semester, students presented their projects again, but this time to their advisors and readers, and any other person who attended the session. This session was really effective in bringing fresh perspectives into the conversation and highlighting areas in each project that needed clarity. This was also a unique opportunity to start practicing presentation skills in preparation for the thesis defense.

It wasn’t an easy journey for everyone in that academic research can be hard to grasp the first time it is done, but all the students had a massive evolution in the last four months: all have completed most of the literature review and have started running their studies. Students will present their final thesis in April during the thesis defense. The challenge for me next semester is guiding them through data analysis and writing up of the final manuscript. And prepare them for the final presentation! Looking forward to it!

Leave a Reply