Teaching my Imagination, Well-Being, & Happiness elective course left me with many learnings. On the one hand, it was beneficial for a few students. One of them realized “how valuable imagination can be” — not just for design work, but for navigating life with a little more softness and flexibility.” Their evolution was documented in their Imagination Journal and it was extremely humbling to witness. Another student learned that “imagination isn’t just about dreaming big things,” but rather “it is also a tool to survive the small, tough moments. It helps you keep going, stay grounded, and feel a little bit happier even when everything feels heavy.” On the other hand, many students did not find the course valuable or understand the connection between imagination and happiness.

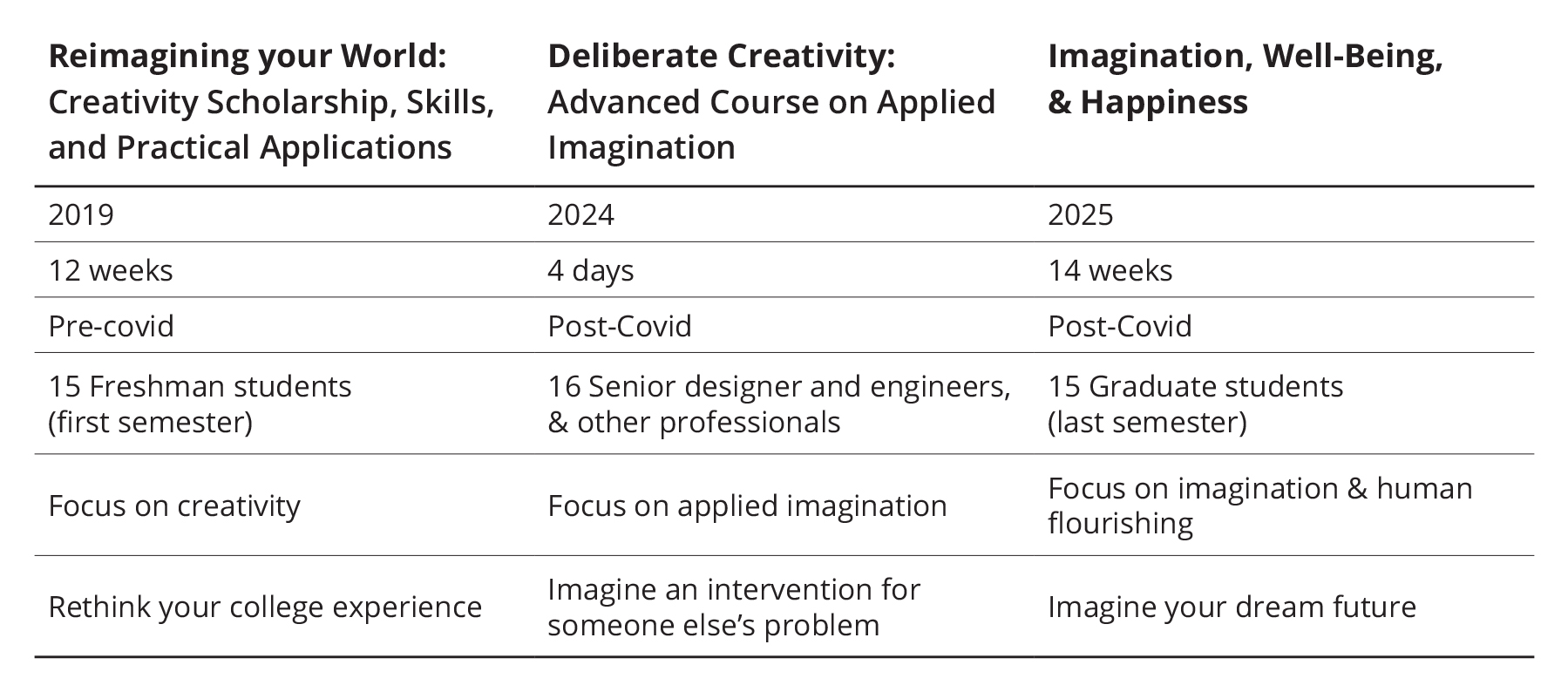

Comparing this course with two other ones — last Summer’s 4-day workshop in Spain and my Freshmen seminar in 2019 at Princeton — the experience with this one was less rewarding. As shown in the Table below, the three courses mostly differed on the goal and focus of the core project with the first two not digging as much into emotional well-being and inner development. While reflective elements and activities were part of these experiences, the focus was perhaps less personal or deep.

Like my other courses, the 14-week elective course was structured into two parts: (1) learning key theories, concepts, and skills (six weeks), and (2) applying them into a three-part project (eight weeks). In total, 12 graduate design students and three undergraduates signed up.

Barriers to transformative learning

Despite the course description clearly articulating the goal and focus, on Day 1, I emphasized that this was not a design course, rather the focus was going to be on emotional well-being and inner development. Then, we did a series of imagination and creativity exercises to which most of students’ responses were as expected:

- Coloring exercises: all the students colored within the lines of the template

- Ideal weekend: students’ dreams were to be productive, complete their to-do list, or have more time to do course work

However, after this class, the experience unfolded very differently from the other two courses. Unfortunately, the following five behaviors became the common denominator of the course:

- Lack of interest: Each week, at least three or four students were absent; a fifth of the students missed three or more classes. I only taught the complete cohort twice in the semester (weeks 12 and 14). This made it very hard to build community or a safe space as well as to plan exercises. Concepts needed to be explained multiple times.

- Lack of attention: Most of the time, students were on their phones or laptops (despite having said on multiple days not to use devices). They completed exercises as fast as possible so they could return to their “other” activity.

- Lack of motivation: Most students showed no interest in the project, in challenging themselves with the Think-Up activities, in generating novel ideas, or in better understanding why they were feeling uncomfortable with open-ended exercises. They had no motivation for dreaming, playing, or imagining. They did not see the point.

- Lack of understanding: Most of the students did not see the value of focusing on inner development rather than on creating a traditional design solution. The open-ended nature of the project made them feel lost and confused, even leaving the format of the final presentation to their choice trigged anxiety.

- Lack of curiosity: After explaining a new concept or finalizing an exercise, there were no questions from the students — at all! This behavior made extremely hard for me to understand what was unclear for them or what concepts needed more practice or explanation. Or how what changes to make so the experience would be more motivating.

All these behaviors have been discussed in creativity studies and literature as barriers and in the past I had had a few students like these. However, this was the first time that most of the students responded this way. For instance, some of the students’ ideas had amazing potential — but many students did not want to invest the time and effort to keep working on them and make them tangible. Rather, they chose to do superficial changes and rush prototypes which resulted in unsophisticated and meaningless projects. This general attitude also made the ideas of the few students who were committed stand out even more. Unfortunately, because of the lack of a supportive environment in the classroom, these students did not feel comfortable speaking up or asking questions.

Rethinking the roadmap

Fun activities that have been eye-opening for the students in the past were received with apathy and judgment. Questions and moments for reflection were met with silences and stares. Through students’ Imagination Journals, an inability to look inwards, reflect, and pay attention to their needs became apparent. Rather than focusing on themselves and dreaming about what they want, most of them were fixated on creating a new commercial design for a client they could include in their portfolio. Only a few students were able to understand how learnings from this class could greatly enhance their life and their practice. These were the ones who saw in the project an opportunity to develop a unique piece of work.

Teaching an imagination course in this context became very challenging for me. I wondered more than once whether I was doing something wrong. If I was doing more or less similar things as in the past, I also thought about external changes: Are world changes impacting students’ behaviors? Has COVID changed students’ ability to reflect and look inwards? Were students’ behaviors a response to this topic or to any topic?

These signals could also indicate new or stronger mental blocks, barriers, and fears among students. If so, I will probably encounter groups with similar characteristics in the future. How should traditional creativity exercises be adapted? What strategies would be better suited to deal with these populations? What strategies could be used to motivate students? Is focusing on personal projects more challenging than designing for others?

In short, this experience loudly pointed to the need for new approaches, strategies, and skills to teach imagination and creativity, or at least when these concepts are coupled with personal dimensions. Teaching imagination for human flourishing posses different challenges than teaching more traditional creativity courses. Further articulating these challenges and developing pedagogical ways to navigate them are my next steps.

You must be logged in to post a comment.